One of the great

treasures of St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle is the Black Book of the Garter (Fig. 1). Bound

in black leather - hence its name, it contains the history, regulations, and

ceremonies of the illustrious Knights of the Order of the Garter, founded by

King Edward III in 1348.

Fig. 1 The Black Book of the Garter (attributed to Lucas Horenbout),

St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle

St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle

Created in 1534, the

Black Book is attributed to the Flemish artist Lucas Horenbout (or Hornebolte)

who was active as an illuminator of manuscripts and as painter of miniature

portraits at the English court from the 1520's to the 1540's.

As the Black Book was

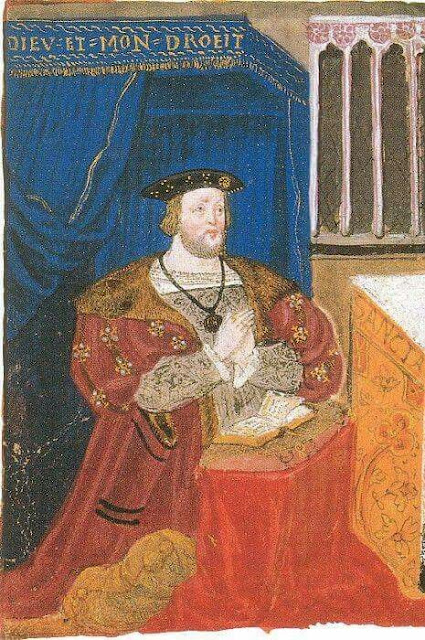

conceived in the reign of Henry VIII, he was naturally featured in it.

While his royal predecessors, from Edward III to Henry VII, had their

likenesses included as well, Henry VIII was accorded pre-eminence. He is shown twice

with the Knights of the Garter (Fig. 2), and then again alone at prayer (Fig. 3).

Not only was Henry, as the Sovereign and as the highest ranking Knight, given due honour,

but so was his current wife Anne Boleyn.

|

| Fig. 2 Henry VIII and the Order of the Knights of the Garter, The Black Book of the Garter (detail) Fig. 3 Henry VIII, The Black Book of the Garter (detail) |

On the 20th page of the

Black Book, a lady, crowned and sceptred, sits enthroned surrounded by

courtiers (Fig. 4). Behind her are six waiting women, and before her on the

left, stands an armoured herald bearing the arms of England on his tabard. On

the right is an 'ancient knight' wearing a rich chain of office. The

accompanying text, written in Latin, identifies her as the Queen Consort who presides over the tournaments the Garter Knights take part in.

'At

this appearance, was his excellent Queen, splendidly arrayed with three hundred

beautiful ladies, eminent for the honour of their birth, and the gracefulness

and beauty of their clothing and dress. For heretofore when jousts,

tournaments, entertainments and public shows were made, in which men of

nobility and valour showed their strength and prowess, the Queen, ladies, and

other women of illustrious birth with ancient knights, and some chosen heralds

were wont to be, and it was supposed that they ought to be present as proper

judges, to see, discern, approve or disapprove what might be done, to

challenge, allot, by speech, nod, discourse, or otherwise to promote the matter

in hand, to encourage and stir up bravery by their words and looks'.[i]

Fig. 4 The Lady of the Garter, The Black Book of the Garter (detail)

The 'excellent Queen'

referred to is Philippa of Hainault, the wife of Edward III. However, a close inspection

of the illumination shows that the sitter wears a large circular pendant at her

bosom. On it are combined letters in gold: A

and R - that is Anna Regina. It is Anne Boleyn as Queen Philippa.[ii]

Rather than the medieval costume of King Edward's reign, the 'Lady of the Garter' and her attendants are in fashions of the Tudor court. The old knight is in a doublet and gown of the time of Henry VIII, while the waiting women wear dresses typical of the 1530's with low squared necklines. Five of them sport rounded French hoods, while a lady on the left has a gabled English one. Anne Boleyn too wears as an English style headdress, and is robed in cloth of gold; a dress very similar to that seen on Henry VIII's subsequent wife Jane Seymour (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Jane Seymour (by an Unknown Artist), Society of Antiquaries

By updating Philippa of

Hainault and her court to the 16th century, Horenbout was following an artistic

convention of contemporizing the past (as in seen in numerous works of art of the

Middle Ages and of the Renaissance where historical and Biblical figures are

shown in modernized clothes and settings). As well, he was also creating a backdrop where he could pay tribute to the present Queen by having her stand in for

Philippa. Even though Anne Boleyn was not known to have been celebrated

as a Lady of the Garter as Philippa and successive English queens were - the

practice of including ladies in Garter rituals seemed to have fallen by the

wayside by the reign of Henry VIII[iii] -

she was still deemed worthy as Queen of England for inclusion in the Black

Book.

By assuming the part of

Philippa of Hainault, Anne Boleyn could also emulate her qualities. Philippa

was described by the chronicler Jean Froissart as 'the most gentle Queen, most liberal, and most courteous that

ever was Queen in her days'. She was especially remembered as the lady

merciful, who had begged her husband the King to spare the lives of the

burghers of Calais. Philippa was also recognized as a patroness of learning. The

Queen's College, Oxford, was founded in her honour. Most importantly, as Philippa was the mother of numerous

children, including five sons who lived into adulthood, Anne was expected to be

just as fertile to safeguard the Tudor dynasty.

As Anne Boleyn was

Philippa in the Black Book, did Henry VIII see himself as Edward III? No,

rather he saw himself as another great king. The book contains a standardized

image of Edward III, but that of Henry V is clearly Henry VIII himself (Fig. 6).

But why Henry V and not Edward III? Though the Black Book lauds the latter as

the founder of the Order and as 'one of the most invincible Princes that ever

sat upon the English Throne',[iv]

Henry VIII might have taken a more sober assessment of Edward's triumphs. The

King who had won renown at Crécy and Poitiers, was also the same who later lost

his territories in France, mourned his son and heir Edward the Black Prince who

tragically predeceased him, and found himself dominated by his grasping

mistress Alice Perrers and her unpopular faction. That said, Henry V, as the great

hero of Agincourt, and whom the Black Book extols as 'the most invincible prince' and 'most

excellent in all kinds of virtue',[v]

probably had more appeal to Henry VIII. Unlike Edward III who slipped

into decline in his later years, Henry V died relatively young at the age of 36,

leaving a successful legacy behind of martial achievements which Henry VIII was

most eager to follow. Besides Henry VIII's identification with Henry V, it should be noted that his likeness also appears in that of his grandfather Edward IV in the Black Book.

With the likeness of

Henry VIII used for that of Henry V, how good is that of Anne Boleyn? While the

faces of her attendants and those of many others in the Black Book are clearly

individualized and meant to depict actual persons, Anne's is admittedly

disappointing in its blandness.[vi] Evidently, Horenbout was more interested in presenting her as an idealized icon of majesty (for instance, notice how the figure is considerably taller in comparison to her courtiers), anticipating the stylized portraits of her daughter Elizabeth I. Still, what can be seen is that the artist depicted Anne with a long oval face and

a pointed chin; features comparable to the well known 'B' pendant type portrait

of Anne (Fig. 7) which was most probably originated by Horenbout as well[vii],

to a medal of her cast in 1534 (Fig. 8), and to an Elizabethan enamel-on-gold locket

ring portrait (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7 Anne Boleyn (by an Unknown Artist), Hever Castle

Fig. 8 Anne Boleyn (by an Unknown Artist), The British Museum

Fig. 9 Locket ring (by an Unknown Artist), The Chequers Trust

Anne Boleyn's inclusion in the Black Book, and the making of her portrait medal, was probably in the earlier part of 1534. She appeared to be pregnant, and the royal couple were looking forward to a boy this time. But by summer, Anne had either suffered a miscarriage or it was a phantom pregnancy.

Despite being Henry

VIII's most famous wife, Anne Boleyn's portraiture remains lacking. The two Hans

Holbein drawings said to be of her are suspect,[viii]

and the famous 'B' pendant portraits are probably all Elizabethan or later. However,

with the recognition of the Black Book's Lady of the Garter as Anne Boleyn, it is

hopeful that more images of Anne made in her own lifetime, besides just the 1534 medal, are still yet to

be discovered.

[i] J.

Anstis et al, The Register of the Most

Noble Order of the Garter, 2 vols. (London, 1724), Vol. 1, p. 32.

[ii]

That the sitter was Anne Boleyn was first noticed by Sir George Scharf, the Director

of the National Portrait Gallery, in a commentary about the portraiture of

Henry VIII's six wives by John Gough Nichols. See: G. Scharf, 'Notes on several of the Portraits described in the

preceding Memoir, and on some others of the like character', Archaeologia, Vol. 40, Issue 01, January

1866, p. 88. Regarding the A. R pendant, a variant of it, a 'broach having the letters R. A. in diamonds' was recorded among Anne's possessions': Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, XII (ii), no. 1315.

[iii] 'Ladies of the Garter: Image of the month', website

of The College of St. George, Windsor Castle: https://www.stgeorges-windsor.org/archives/archive-features/image-of-the-month/title1/Ladies-of-the-Garter-Image-of-the-month.html (accessed April, 2017).

[iv]

J. Anstis et al, Register, p. 1.

[v] J.

Anstis et al, Register, p. 64 and p.

65.

[vi] 'For

example, Horenbout's well observed likeness of Henry Percy, Earl of

Northumberland, in his illustration of the Garter procession. It was later

served as a basis for an enlarged portrait (Collection of the Duke of

Northumberland). As for the Lady of the Garter, 'not much character in her

countenance', Scharf opined: Archaeologia,

p. 88.

[vii]

R. Hui, 'A Reassessment of Queen Anne Boleyn’s Portraiture', Tudor Faces blog (Jan., 2015; originally

posted in Jan. 2000): http://tudorfaces.blogspot.ca/2015/01/a-reassessment-of-queen-anne-boleyns.html

(accessed April, 2017).

[viii]

R. Hui, 'A Reassessment of Queen Anne Boleyn’s Portraiture'. Also E. Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, pp. 41-44. As well, miniatures said to be of Anne (in the Royal Ontario Museum and in the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch) may be that of her sister Mary Boleyn. See: R. Hui, 'Two New Faces: the Hornebolte Portraits of Mary and Thomas Boleyn'?, Tudor Faces blog (Oct., 2011): http://tudorfaces.blogspot.ca/2011/10/two-new-faces-hornebolte-portraits-of.html (accessed April, 2017).

It is interesting to note the Imperial Crown above the gable hood worn by Anne Boleyn in her depiction as Queen Phillipa. This inclusion demonstrates Henry's increasing bid during the 1530s to claim precedent for the English king's absolute power within the realm, including total authority over the Church in England, in defiance of the Church of Rome. As his anointed queen Anne shared this God-given right, and so would the child that she was carrying when this illustration was made. You can see Henry and Anne's prevalent use of the Imperial Crown in the King's College Chapel choirscreen, also created at this time. The claim to imperial power delivers the potent message of intent that Henry and Anne were formulating towards the Church of Rome, and those still adhering to it's authority.

ReplyDeleteI agree that the long face, pronounced chin, and even the arch of her eyebrows in the Black Book depiction is similar to Anne's portrait in the Moost Happi medal. Her body is seated in the wide-legged posture that emphasises the curve of her belly, a pose often used in images of the Virgin Mary. Presumably this image, like the Moost Happi medal, was commissioned during the first half of 1534 when Anne was still believed to be pregnant with a healthy male heir to the English throne.

There IS one other depiction of Anne which was indisputably created during her lifetime - the illustrated seating plan of Anne's coronation feast at Westminster Abbey. This depicts her after having been anointed the Queen of England, wearing (for the first time) an Imperial Crown which demonstrated that she now shared absolute power with Henry over the realm. It's a simple line drawing, almost cartoon-like in its simplicity, but I love it's joyful freshness, and what it represents.

For the illustration of Anne's coronation feast see: MS Harley 41,f.12r. British Library, London.

For my analysis of the imagery on Henry and Anne's choirscreen see: http://www.sculptureinstone.co.uk/Notesandqueries2014.pdf

For my systematic list of the imagery on the King's College choirscreen see: http://www.lucychurchill.com/userfiles/IndexofImageryonKingsCollegeChapelChoirScreen1.pdf

Roland, I'm becoming more and more convinced that it is Anne Boleyn. With the book being created in 1534, it makes perfect sense for Henry VIII to depict his pregnant wife as the Lady of the Garter in this way to celebrate her pregnancy and their hopes for a son this time.

ReplyDeleteI know that it has been argued that AR could be for Anglia Regina but that doesn't make sense as it would be more likely to be RA - Regina Anglica/Anglia/Angliae - and I haven't seen any mention of Henry's consorts using AR or even RA as a motif in jewellery or costume like that.

Lucy's point regarding the imperial crown is very persuasive too.

Interesting!

Great article, and compelling arguments! I am so hopeful that more of these forgotten images will be rediscovered and analysed, and that we will find many more lost faces like Anne Boleyns. Or that some old pictures and drawings will submerge from private collections over time and that History will unveil some more of it's mysteries! Thank you

ReplyDeleteAnna Regina

ReplyDelete